Malware is Everywhere

Malware (or malicious software) is really the key term here. Malware’s definition is at the eyes of the beholder, but I use the term generally as software that you do not want. It can include everything from the destructive virus to the annoying adware popup asking you to clean your PC.

Most malware seems to come in the form of those unwanted software add-ons that seem to come with any free download on the internet.

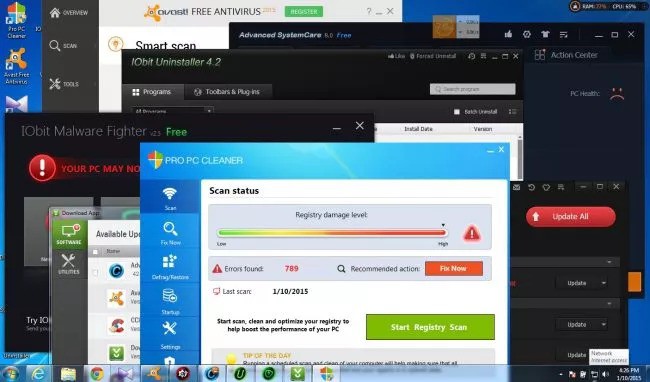

Downoading the top ten downloads on CNET’s download.com’s site, according to Lowell Heddings, the “How-To Geek” your desktop, will look something like this: CNET is a fairly “reputable” website and Download.com has been around since, well, as long as most people can remember the modern internet, yet somehow these add-on toolbars, PC cleaners, virus detectors, and malware removers seem to just be bloated, annoying, and frankly malicious software.

CNET is a fairly “reputable” website and Download.com has been around since, well, as long as most people can remember the modern internet, yet somehow these add-on toolbars, PC cleaners, virus detectors, and malware removers seem to just be bloated, annoying, and frankly malicious software.

How is “Malware” Bundles Even Allowed?

Heddings further points out that Download.com’s own “Malicious Software Policies” specify their representation that their software that is listed do not contain “viruses, Trojan horses, malicious adware, spyware, or other potentially harmful components.” Most importantly, no software is listed that “installs without notice and without the user’s consent.”

It seems that publishers and directories like CNET take the position that it is not a malicious adware, spyware, or potentially harmless if the user consents to the software. If you actually take the time to read those End User Licenses Agreements that many of us, including us lawyers, tend to not read, you would see that you are consenting to the download and installation of all those random junk toolbars and software.

Malware Bundling Goes Undetected Everywhere

It is when these kinds software are not properly disclosed or even mistakenly included in bundled software or pre-installed systems that the law actually has something to say.

Take Lenovo’s recent debacle after researchers found their devices came with pre-installed adware from a company called Superfish. In that case, user’s new laptops came with popups displaying scantily clad women as alleged in a class action lawsuit against Lenovo.

Mobile apps are not any less vulnerable. Professional hackers are targeting the Apple’s App Store and Google Play Store to inject its hidden malware into a usable app.

Bundled Software Makes Money for Developers

There are plenty of networks (including CNET) that encourage you to give your well-built software out for free in exchange for bundling software with yours. They all include a pay-per-download or pay-per-install model that can be very attractive to a software developer that would otherwise not make a dime to giving software away for free.

It is a fair assumption that most of these platforms will comply with proper disclosures needed to the end user, but rarely do these arrangements exceed the bare minimum.

Potential Liability of Software Bundling

For the most part, software platforms have the know-how to ensure proper disclosure to the user. It is very easy to slap together a shrink-wrap agreement that no one is going to read and they.

Part of the problem is that the laws surrounding malware are not very strong. Take for example a lawsuit against an adware vendor that developed a software called “Text Enhance.” That software caused a popup to appear each time the user’s mouse would hover over certain keywords. A claim was brought under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), but the court did not permit the claim to go forward because the damage threshold of $5,000 was not met and that the court is unable to aggregate the harm to other users.

The CFAA has some of the sharpest teeth in combating this issue, but how useless it would be to have to reach that $5,000 for each single user.

Slightly more useful are the civil claims that may be available under state laws that include trespass to personal property or violations of unfair competition. Unfortunately, the damages aspect to these types of claims are usually equally useless unless it can be turned into a class action, such as the case in Lenovo.

It would seem the answer to this problem (assuming you agree it is one), is not a legal one.

The real question is what legitimately operating company wants to be associated with bloatware or bundled useless adware? Developers’ negative reputation may be enough to deter most and end user diligence for the rest.

Going After the Real Bad Actors

Assuming you can differentiate those unwanted software programs that get bundled with other software slowing down your computer and just plain spyware and viruses, how do you go after the real criminals? The biggest problem is that the laws of the United States do not apply the laws of Nigeria, China or Russia (not to pick on any one country). Most of the real malicious software is distributed internationally.

Extradition treaties do not apply until you figure out who committed the crime–which is impossible if you have no authority to investigate across international borders.

With very little legal recourse, if you are busy unscrambling an attacked network or infested personal computer, you have already lost. No lawyer is going to get you out of this one. Call tech support.

![Law in the Digital Age: Exploring the Legal Intricacies of Artificial Intelligence [e323]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/WhatsApp-Image-2023-11-21-at-13.24.49_4a326c9e-300x212.jpg)

![Unraveling the Workforce: Navigating the Aftermath of Mass Layoffs [e322]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Untitled-design-23-300x212.png)

![Return to the Office vs. Remote: What Can Employers Legally Enforce? [e321]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Pasha_LSSB_321_banner-300x212.jpg)

![Explaining the Hans Niemann Chess Lawsuit v. Magnus Carlsen [e320]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/LAWYER-EXPLAINS-7-300x169.png)

![California v. Texas: Which is Better for Business? [313]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Pasha_LSSB_CaliforniaVSTexas-300x212.jpg)

![Buyers vs. Sellers: Negotiating Mergers & Acquisitions [e319]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Pasha_LSSB_BuyersVsSellers_banner-300x212.jpg)

![Employers vs. Employees: When Are Employment Restrictions Fair? [e318]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Pasha_LSSB_EmployeesVsEmployers_banner-1-300x212.jpg)

![Vaccine Mandates Supreme Court Rulings [E317]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/WhatsApp-Image-2022-02-11-at-4.10.32-PM-300x212.jpeg)

![Business of Healthcare [e316]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Pasha_LSSB_BusinessofHealthcare_banner-300x212.jpg)

![Social Media and the Law [e315]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/WhatsApp-Image-2021-10-06-at-1.43.08-PM-300x212.jpeg)

![Defining NDA Boundaries: When does it go too far? [e314]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Pasha_LSSB_NDA_WordPress-2-300x212.jpg)

![More Than a Mistake: Business Blunders to Avoid [312] Top Five Business Blunders](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Pasha_LSSB_Blunders_WP-1-300x212.jpg)

![Is There a Right Way to Fire an Employee? We Ask the Experts [311]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Pasha_LSSB_FireAnEmployee_Website-300x200.jpg)

![The New Frontier: Navigating Business Law During a Pandemic [310]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Pasha_LSSB_Epidsode308_Covid_Web-1-300x200.jpg)

![Wrap Up | Behind the Buy [8/8] [309]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Pasha_BehindTheBuy_Episode8-300x200.jpg)

![Is it all over? | Behind the Buy [7/8] [308]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/iStock-1153248856-overlay-scaled-300x200.jpg)

![Fight for Your [Trademark] Rights | Behind the Buy [6/8] [307]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Fight-for-your-trademark-right-300x200.jpg)

![They Let It Slip | Behind the Buy [5/8] [306]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Behind-the-buy-they-let-it-slip-300x200.jpg)

![Mo’ Investigation Mo’ Problems | Behind the Buy [4/8] [305]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/interrobang-1-scaled-300x200.jpg)

![Broker or Joker | Behind the Buy [3/8] [304] Behind the buy - Broker or Joker](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Joker-or-Broker-1-300x185.jpg)

![Intentions Are Nothing Without a Signature | Behind the Buy [2/8] [303]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/intentions-are-nothing-without-a-signature-300x185.jpg)

![From First Steps to Final Signatures | Behind the Buy [1/8] [302]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/first-steps-to-final-signatures-300x185.jpg)

![The Dark-side of GrubHub’s (and others’) Relationship with Restaurants [e301]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/When-Competition-Goes-Too-Far-Ice-Cream-Truck-Edition-300x201.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown of Internet Law & the Subscription Business Model [e300]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Ultimate-Legal-Breakdown-of-Internet-Law-the-Subscription-Business-Model-300x196.jpg)

![Why the Business Buying Process is Like a Wedding?: A Legal Guide [e299]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/futura-300x169.jpg)

![Will Crowdfunding and General Solicitation Change How Companies Raise Capital? [e298]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Will-Crowdfunding-and-General-Solicitation-Change-How-Companies-Raise-Capital-300x159.jpg)

![Pirates, Pilots, and Passwords: Flight Sim Labs Navigates Legal Issues (w/ Marc Hoag as Guest) [e297]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/flight-sim-labs-300x159.jpg)

![Facebook, Zuckerberg, and the Data Privacy Dilemma [e296] User data, data breach photo by Pete Souza)](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/data-300x159.jpg)

![What To Do When Your Business Is Raided By ICE [e295] I.C.E Raids business](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ice-cover-300x159.jpg)

![General Contractors & Subcontractors in California – What you need to know [e294]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/iStock-666960952-300x200.jpg)

![Mattress Giants v. Sleepoplis: The War On Getting You To Bed [e293]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/sleepopolis-300x159.jpg)

![The Harassment Watershed [e292]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/me-2-300x219.jpg)

![Investing and Immigrating to the United States: The EB-5 Green Card [e291]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/eb-5-investment-visa-program-300x159.jpg)

![Responding to a Government Requests (Inquiries, Warrants, etc.) [e290] How to respond to government requests, inquiries, warrants and investigation](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/iStock_57303576_LARGE-300x200.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Employee Dress Codes [e289]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Ultimate-Legal-Breakdown-Template-1-300x159.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Negative Online Reviews [e288]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Ultimate-Legal-Breakdown-Online-Reviews-1-300x159.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Social Media Marketing [e287]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ultimate-legal-breakdown-social-media-marketing-blur-300x159.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Subscription Box Businesses [e286]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ultimate-legal-breakdown-subscription-box-services-pasha-law-2-300x159.jpg)

![Can Companies Protect Against Foreseeable Misuse of Apps [e285]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/iStock-505291242-300x176.jpg)

![When Using Celebrity Deaths for Brand Promotion Crosses the Line [e284]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/celbrity-300x159.png)

![Are Employers Liable When Employees Are Accused of Racism? [e283] Racist Employee](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Are-employers-liable-when-an-employees-are-accused-of-racism-300x159.jpg)

![How Businesses Should Handle Unpaid Bills from Clients [e282] What to do when a client won't pay.](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/How-Businesses-Should-Handle-Unpaid-Bills-to-Clients-300x159.png)

![Can Employers Implement English Only Policies Without Discriminating? [e281]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Can-Employers-Impliment-English-Only-Policies-Without-Discriminating-300x159.jpg)

![Why You May No Longer See Actors’ Ages on Their IMDB Page [e280]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/IMDB-AGE2-300x159.jpg)

![Airbnb’s Discrimination Problem and How Businesses Can Relate [e279]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/airbnb-300x159.jpg)

![What To Do When Your Amazon Account Gets Suspended [e278]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/What-To-Do-When-Your-Amazon-Account-Gets-Suspended-1-300x200.jpg)

![How Independent Artists Reacted to Fashion Mogul Zara’s Alleged Infringement [e277]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/How-Independent-Artists-Reacted-to-Fashion-Mogul-Zaras-Alleged-Infringement--300x159.jpg)

![Can Brave’s Ad Replacing Software Defeat Newspapers and Copyright Law? [e276]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Can-Braves-Ad-Replacing-Software-Defeat-Newspapers-and-Copyright-Law-300x159.jpg)

![Why The Roger Ailes Sexual Harassment Lawsuit Is Far From Normal [e275]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/WHY-THE-ROGER-AILES-SEXUAL-HARASSMENT-LAWSUIT-IS-FAR-FROM-NORMAL-300x159.jpeg)

![How Starbucks Turned Coveted Employer to Employee Complaints [e274]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/iStock_54169990_LARGE-300x210.jpg)