- Introduction

- Navigating the Risk Matrix

- Dissecting Minority Protections

- The Essence of Minority Rights

- Pre-emptive rights

- Right of first refusal

- Liquidation Preferences

- Co-Sale Rights

- Right To Demand An Initial Public Offering (IPO)

- Reasons Behind Minority Protections

- Protecting Against Value Dilution in Future Rounds

- Maintaining Some Level of Control Over Key Company Decisions

- Ensuring an Exit Pathway that Safeguards Investment Returns

- Preventing Majority Stakeholders from Selling to Unfavorable Third Parties

- Establishing Protective Measures Against Potential Mismanagement

- Tailoring to Objectives

Introduction

In the intricate world of investment structures, the myriad of templates, guidelines, and conventional wisdom available to investors and companies can often seem like an overbearing maze. Yet, when we strip away the layers of complexity, a fundamental truth emerges: it all boils down to the core conceptual factors driving the decisions.

Imagine a builder approaching a construction project. While they may have an array of tools at their disposal, understanding the terrain, the desired outcome, and the material properties will guide their tool choices. Similarly, in the vast construction of investment structures, understanding the foundational, conceptual factors becomes the compass, directing us to the most optimal arrangements. It’s not merely about how the structure is built but understanding the why behind each brick and beam.

By centering our approach on these underlying motivations and objectives, the labyrinth of choices becomes a logical path. This article seeks to illuminate that path, emphasizing that by first grasping the key conceptual determinants, the structures that best serve your unique goals will become self-evident. Dive in with us, as we venture beyond the generic templates, and embark on a journey of tailored investment crafting, rooted in the clarity of conceptual understanding.

The Conceptual Compass of Investment Structuring

Venturing into the depths of investment, we find that there are several anchoring points that one must consider. First, Navigating the Risk Matrix – discerning how risk is both perceived and allocated. Second, the intricacies of Valuation – deducing the real worth of an investment, which is an amalgamation of market alternatives, competitor offerings, and innate company value. Then, the dynamics of Control – striking a balance between oversight and autonomy. We also touch upon the protective essence of Minority Rights, which act as shields against potential inequities. Beyond the black and white of investment terms, it’s essential to understand the underlying Reasons Behind These Rights, the heartbeat of many investment clauses. And lastly, every investment story is colored by the unique perspectives of both the investor and the recipient, hence the importance of viewing through both the Investor’s Lens and the Recipient’s Reality. As we delve deeper, these seven pillars form the bedrock upon which tailored investment structures stand, ensuring a foundation that is both robust and flexible to the nuances of individual objectives.

Navigating the Risk Matrix

Allocation of Risk

The ebb and flow of investments often lead to the shores of risk. In the grand tapestry of investment structuring, understanding how risk is allocated can dictate the entire course of an investor’s journey. It’s not merely about risk-taking, but about when, how, and in what order investors will see returns—or potentially face losses.

Senior Debt Arrangements

This traditional structure is akin to the old reliable lighthouses guiding ships safely to the harbor. A senior debt implies that in the event of liquidation or bankruptcy, these debt holders get paid before other investors. Historical tidbit: During the 2008 financial crisis, many institutions scrambled to ensure their debt was classified as ‘senior’ to prioritize their repayment. For companies, this can be a double-edged sword. While senior debt might be more accessible due to its lower risk for lenders, it can tie up critical assets as collateral. The tip? Always evaluate the trade-offs between easy access to capital and the stringent requirements that come with it.

Participating Preferred Stock

Think of this as an investor wanting the best of both worlds. They get their initial investment back and then some, through a share of the company’s profits. It’s a way to prioritize investor repayment while allowing them to benefit from the company’s success. A notable example is Microsoft’s $240 million investment in Facebook in 2007. Their deal was structured as participating preferred stock, which, given Facebook’s meteoric rise, turned out to be a masterstroke. For companies, this structure can be appealing as it aligns investor interests with the company’s growth. The catch? Ensure you’re not giving away too much of the pie.

Convertible Notes

This is a deferred decision instrument, a bet on the future. Instead of deciding the company’s valuation now, investors and the company agree to decide later, during a future investment round. Dropbox’s early funding rounds heavily utilized convertible notes, which allowed them to quickly access funds without lengthy valuation debates. It’s a swift tool, especially for startups in their nascent stages. Pro tip: Ensure the conversion terms, like valuation caps or discounts, are clear to avoid future disputes.

Understanding Convertible Notes

Convertible notes are a type of short-term debt that can be turned into equity, typically during a future financing round. Here’s a quick breakdown:

Purpose:

Startups often use convertible notes to raise initial funds without immediately setting a valuation. This deferment allows them to access capital quickly without the complexities of valuing a young, unproven company.

Conversion Triggers:

These notes generally convert into equity during a specified event, usually a subsequent funding round. The terms of the conversion—like the discount rate or valuation cap—pre-determine how much equity the note will convert into.

Benefits for Investors:

Convertible note holders get the protection of debt (they’re typically repaid before equity holders if the company dissolves) and the potential upside of equity if the company does well.

Benefits for Startups:

Beyond the quick access to capital, startups can delay setting a valuation until they have more traction, which could lead to a higher valuation in the future.

Remember, like all investment instruments, convertible notes come with risks and rewards. Both investors and startups should understand the terms thoroughly before proceeding.

Royalty-based Financing

In essence, investors are betting on the product, not just the company. They get repaid as a portion of the revenue from the product’s sales. Biotech firms, especially those in the drug discovery phase, often utilize this to great effect. When they do strike gold—a blockbuster drug—the returns can be monumental. However, it’s crucial to ensure a clear understanding of sales metrics and royalty rates.

Revenue-based Financing

Similar to royalty-based, but broader. The investor gets a cut of the company’s overall revenue up to a predefined multiple of the initial investment. Historically, tech startups, wary of diluting equity, have found this appealing. Basecamp, a software company, once famously utilized this method, allowing them to scale without traditional VC funding. A word to the wise? Establish clear definitions of revenue and ensure that repayment terms don’t choke the company’s growth.

As we sail through these waters, understanding how to allocate risk is pivotal. Each structure comes with its own navigational challenges. By analyzing historical precedents and being clear about priorities, investors and companies alike can chart a course that’s both safe and lucrative.

Valuation Conundrums

Understanding the true value of an investment can sometimes feel like catching smoke with bare hands. It’s elusive and multifaceted, shaped by myriad external and internal factors. The art of valuation isn’t just an exercise in numbers but in foresight, strategy, and context. The market speaks a language of potential returns, competitor benchmarks, and intrinsic company value, among other things. Let’s unpack these dimensions, shedding light on the various methods investors and companies use to arrive at a sound investment valuation.

Opportunity Cost Analysis

The age-old adage, “Time is money,” extends its reach into the investment world. Every penny invested in a company is a penny not invested elsewhere. Investors often measure the potential returns of an investment against its alternatives in the market. For instance, if one could invest in a stable bond yielding a 5% annual return, any equity investment should ideally offer a higher potential return, compensating for the added risk. Warren Buffett’s decision to invest in Apple in 2016 serves as a classic example. He saw an opportunity in Apple that he believed would provide a better return than other market alternatives.

Competitor Funding Terms

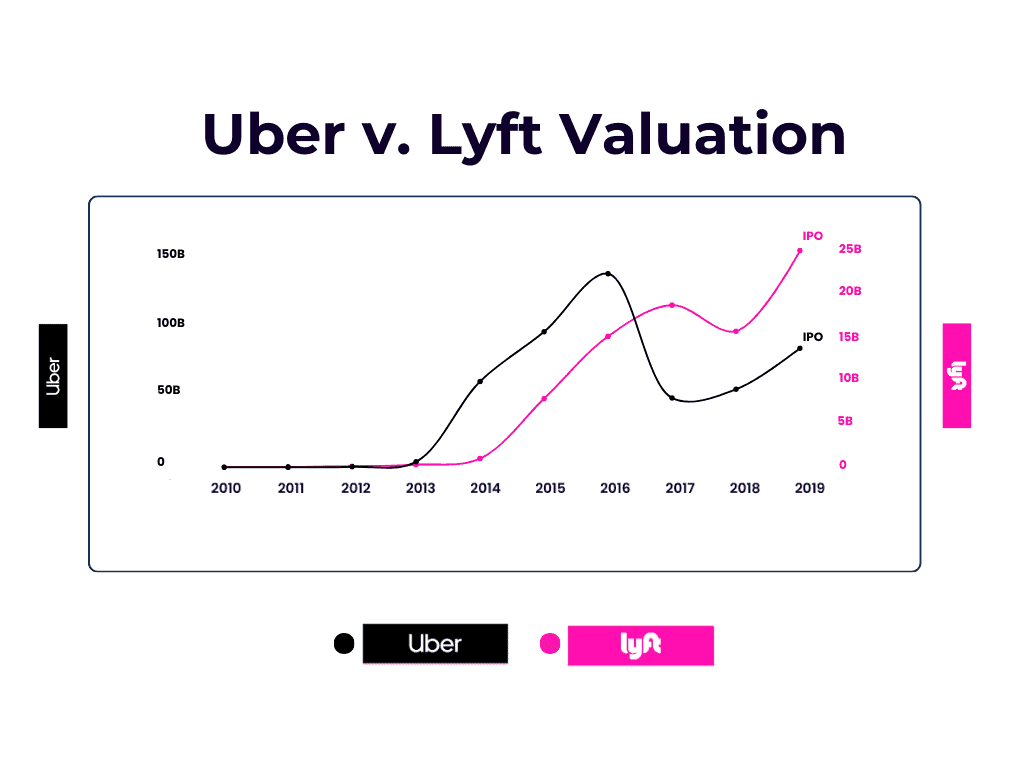

In a world where businesses vie for the attention of a limited pool of investors, understanding what terms competitors are securing can provide a clear market benchmark. This not only helps in setting realistic expectations but also ensures that an investment deal isn’t skewing too far from the industry norm. Take the ridesharing industry; Uber’s funding rounds and valuations set a precedent that other competitors like Lyft and Didi had to consider when they sought funding. They had to position themselves either as better investment opportunities or reconcile with potentially less favorable terms.

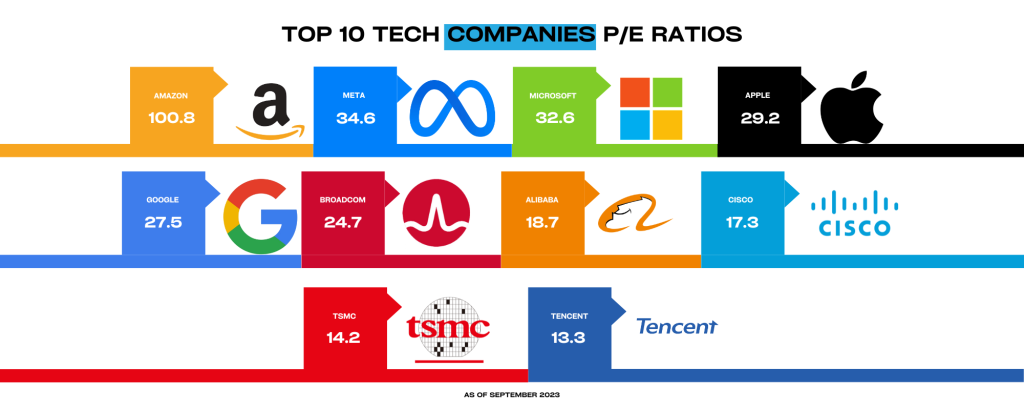

Historical Earnings Valuation

Sometimes, the past can be a good predictor of the future, especially when it comes to mature businesses with stable earnings. The price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, which divides a company’s stock price by its earnings per share, has long been a staple in the investor’s toolbox. A high P/E might suggest overvaluation, while a low one could hint at undervaluation. The Coca-Cola Company, with its consistent earnings over the decades, often gets its valuation rooted in this method. Though not infallible, it offers a grounded perspective, especially when compared against industry averages.

Discounted Cash Flow

Projecting future revenues and discounting them to present value is akin to gazing into a crystal ball, albeit one grounded in data and analytics. The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method assesses the future earnings potential of a company and brings it to today’s terms, offering a glimpse of what an investment might be worth down the line. Amazon’s early years, marked by heavy investments and thin profits, showcased a company rich in future potential, a potential many discerned using DCF. As the e-commerce giant’s growth story unfolded, those valuations rooted in future cash flows proved prescient.

Exit Strategy Valuation

The endgame is often as critical as the game itself. Investors invariably ponder their exit – the moment they can cash in on their investment. By considering potential future events, like a company’s acquisition or IPO, one can work backwards to determine the present value of an investment. Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp for $19 billion in 2014 serves as a reminder of this. While the messaging app wasn’t earning revenues to justify such a valuation traditionally, the potential synergies and future monetization strategies it could unlock for its acquirer made the price tag palatable.

Valuation is both an art and a science. By understanding these methods and the nuances they carry, investors and companies can navigate the intricate dance of deal-making with greater clarity and conviction.

Control Dynamics

In the intricate ballet of investments, control emerges as a pivotal theme. It’s not just about how much of the pie you own; it’s about the influence you wield over its direction and flavor. Investors, especially those who stake significant amounts, often seek assurances that their capital is steered wisely. Yet, businesses need enough room to pivot, adapt, and innovate. This delicate equilibrium between investor oversight and operational freedom is what defines control dynamics.

Board Seats

The offer of a seat on the board often serves as a symbol of trust and shared direction. It provides investors with a vantage point to influence the strategic direction of a company. For instance, when Yahoo invested in Alibaba in 2005, Jerry Yang, Yahoo’s co-founder, took a seat on Alibaba’s board. This not only allowed Yahoo a closer view of Alibaba’s operations but also signaled a collaborative approach. Companies need to consider how many seats they’re willing to offer and the implications for company direction.

Veto Rights

Veto rights arm investors with a protective mechanism. They can limit certain pivotal company actions without their express nod. Historically, when Skype was sold by eBay to Microsoft, some early investors had veto rights that influenced deal terms and ensured they received a significant part of the bounty. However, companies need to tread carefully here. Offering too many veto rights can hamper swift decision-making and agility, potentially stifling growth and responsiveness.

Drag-along and Tag-along Rights

These rights exist to protect investors during major corporate events, like buyouts. Drag-along rights enable majority stakeholders to “drag” minority ones into a sale, ensuring a unified selling front. Conversely, tag-along rights allow minority investors to “tag along” in a sale, ensuring they get similar terms. When Facebook acquired WhatsApp, tag-along rights ensured that even smaller shareholders benefited handsomely from the deal. Companies should assess the balance of power these rights introduce and their alignment with long-term business goals.

Anti-Dilution Clauses

Designed to maintain an investor’s proportionate ownership, anti-dilution clauses come into play when new shares are issued. A renowned instance is when Twitter’s early investors, like Union Square Ventures, benefited from anti-dilution provisions during subsequent funding rounds. These clauses ensured that their ownership stakes weren’t significantly diluted despite additional investments. Companies, however, should weigh the potential impacts of such clauses on future fundraising endeavors and operational flexibility.

Information Rights

The ability to periodically peek under the hood is crucial for many investors. Information rights guarantee them periodic performance, financial reports, and other essential data. When Google’s parent company, Alphabet, invested in SpaceX, it secured specific information rights, reinforcing transparency and trust. Yet, businesses should ensure that the frequency and depth of disclosure don’t impede operational secrecy or become too onerous to maintain.

As with all aspects of investment, understanding and calibrating control dynamics requires a deep dive into both investor aspirations and company objectives. By threading the needle carefully, companies can ensure they maintain operational latitude while assuaging investor concerns.

Dissecting Minority Protections

The Essence of Minority Rights

Understanding the significance of minority rights in the investment arena is crucial. Often overshadowed by dominant voices, minority stakeholders can find themselves at a crossroads of vulnerability. From the perspective of these smaller players, it becomes paramount to safeguard their interests and ensure a level of protection against the potential overarching dominance of majority stakeholders. These rights act as guardrails, navigating the path of investment while preventing any unforeseen cliffs of disadvantage. Let’s take a closer look at some of the most common minority protections.

Pre-emptive rights

Minority investors often face the danger of having their stakes diluted in subsequent funding rounds. To counter this, pre-emptive rights provide them with the option to purchase additional shares in future rounds, thereby maintaining their ownership percentage. Consider the scenario of early Facebook investor, Eduardo Saverin, who initially had his stake diluted. While the legal battles that ensued are well-known, had there been clearer preemptive rights in place, the scenario might have been vastly different.

The Eduardo Saverin & Facebook Saga

Eduardo Saverin, one of the co-founders of Facebook, serves as a cautionary tale for the significance of minority rights and protections in the world of startups and investments.

In 2004:

Eduardo Saverin and Mark Zuckerberg teamed up to launch what would eventually become the world’s largest social media platform, Facebook. As the initial business manager and chief financial officer, Saverin made an essential contribution to the platform, even investing his own money to keep the project alive in its nascent stages.

The Dilution:

However, as Facebook began to grow and attract more investors, Saverin’s stake in the company was diluted significantly. This was primarily due to a series of agreements and stock restructurings that he allegedly wasn’t fully aware of or had misunderstood. By 2005, Saverin’s approximately 30% stake in Facebook was diluted down to a mere fraction.

The Legal Battle:

Feeling marginalized and betrayed, Saverin sued Facebook and Zuckerberg in 2009. This legal battle culminated in a settlement where Saverin’s co-founder status was reaffirmed, and he received an undisclosed number of shares. Though exact figures remain confidential, it’s estimated that Saverin retains just below 2% of Facebook’s shares.

The Takeaway:

The Saverin-Facebook saga underscores the importance of understanding and negotiating minority protections early on in a venture’s journey. It serves as a vivid reminder for investors and founders alike to ensure they’re not just part of the growth story but are also protected against unforeseen dilutions and corporate decisions.

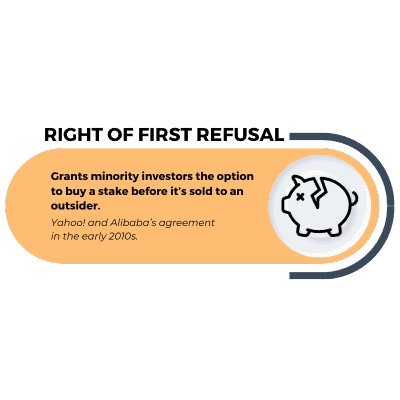

Right of first refusal

Envision being an investor and finding out that a significant share of the company you’ve invested in is being sold to a potentially unfavorable party. The right of first refusal is a protective measure against such scenarios. It grants minority investors the option to purchase any stake before it’s sold to an outsider. This mechanism ensures that minority stakeholders retain some control over who enters the shareholder ecosystem. The tech industry provides numerous anecdotes. For instance, Yahoo! once had an agreement with Alibaba that included a right of first refusal, which became a point of contention during their negotiations in the early 2010s.

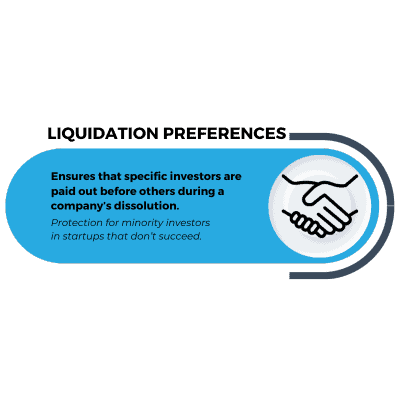

Liquidation Preferences

Liquidation can often be a daunting word in the investment world, particularly for minority investors. Liquidation preferences ensure that in the event of a company’s dissolution, certain investors get paid out before others. It’s like having a VIP ticket to an exclusive event. For many minority investors in startups that didn’t stand the test of time, this right acted as a safety net, ensuring they recouped some, if not all, of their initial investment.

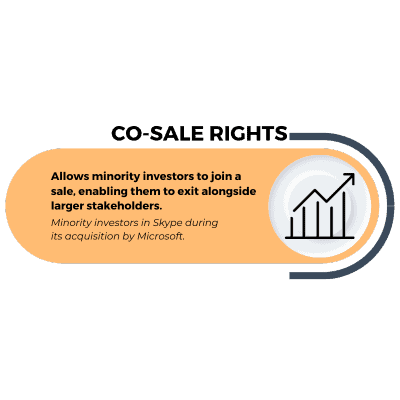

Co-Sale Rights

Imagine being a small investor in a company that’s attracting the attention of bigger players. The fear is often that majority stakeholders might sell their shares, leaving minority shareholders in an unpredictable environment. Co-sale rights come to the rescue, allowing minority investors to join the sale bandwagon, ensuring they have the choice to exit alongside larger shareholders. This was evident in the case of Skype, where certain minority investors utilized their co-sale rights during its acquisition by Microsoft.

Right To Demand An Initial Public Offering (IPO)

Pushing for a company to go public can often be seen from the lens of achieving liquidity. The right to demand an IPO is a potent tool for minority investors, allowing them to champion the cause of going public. While not as common, this right empowers investors to influence the trajectory of a company, possibly leading it to the broad horizons of the public market. Anecdotally, some investors in tech unicorns of the past decade have nudged companies towards an IPO path, looking for broader market validations and lucrative exits.

As we’ve journeyed through these protective layers, it’s evident that the landscape of minority rights isn’t just about legalese and clauses. It’s about ensuring a balanced playing field, where each player, irrespective of their stake size, feels secure and heard.

Reasons Behind Minority Protections

While Minority Rights serve as a safety net for those not in the controlling stake of a company, it’s pivotal to delve into the rationale behind such rights. The pressing concern isn’t merely about having a checklist of rights, but more about the need, intention, and objective behind each one. These rights, although varied, are woven with a common thread: to protect the minority investors from potential inequities, ensuring their voice isn’t lost in the corporate cacophony.

Protecting Against Value Dilution in Future Rounds

Understanding the threat of value dilution is vital. As a company raises more capital, issuing more shares, existing stakeholders might find their ownership percentages dwindling. This was evident during the early years of tech startups where founders, unaware of the intricacies, found themselves with diminished stakes after successive funding rounds. To mitigate this, minority investors often secure preemptive rights, giving them the option to buy new shares in subsequent rounds to maintain their ownership percentage.

Maintaining Some Level of Control Over Key Company Decisions

It’s a tale as old as business itself – an investor’s need for some semblance of control. Without it, the waters of investment can become murky. A classic anecdote lies in the corporate annals of Apple Inc., where Steve Jobs, the visionary founder, was ousted from his own company in 1985. Minority investors, aware of such instances, often push for veto rights. This ensures they have a say, albeit limited, in pivotal decisions that could redefine the course of the company.

Ensuring an Exit Pathway that Safeguards Investment Returns

In the realm of investments, the exit strategy is a beacon that investors move towards. Be it through acquisition, merger, or IPO, they seek assurance that their route out is not only clear but also profitable. The story of Microsoft’s acquisition of Skype in 2011 underscores this. Silver Lake, a minority investor in Skype, leveraged its liquidation preference clause, ensuring a lucrative return on its initial investment upon the acquisition. Liquidation preferences act as navigational tools, directing the sequence and amount of payouts during such exits.

Preventing Majority Stakeholders from Selling to Unfavorable Third Parties

The corporate landscape is riddled with tales of stakeholders selling their stakes to third parties, sometimes to the detriment of minority investors. Such scenarios often lead to shifts in company direction, strategy, or culture, not always favorable to all. To combat this, minority investors often hold the Right of First Refusal. This right ensures that before any stake is sold to an external party, it’s first offered to existing investors, granting them the option to buy and thereby maintaining the company’s existing equilibrium.

Establishing Protective Measures Against Potential Mismanagement

No investor enters a venture anticipating mismanagement, but the prudent ones prepare for it. The overarching fear is that majority stakeholders, with their controlling powers, might take actions unfavorable or detrimental to the company and its minority shareholders. This is where the right to demand an initial public offering (IPO) comes into play. Pushing for the company to go public ensures transparency, adherence to stringent regulations, and a broader scrutiny, serving as a deterrent to potential corporate mismanagement. An echo of this sentiment was seen in the pressure many private unicorn startups faced from minority stakeholders in the past decade to go public, ensuring a more transparent operational terrain.

By unpacking the reasons behind minority rights, investors and companies can ensure that their agreements not only adhere to standard norms but resonate with the objectives and concerns that underpin these norms. Only then can an investment structure truly be robust, safeguarding interests while fostering growth.

Tailoring to Objectives

The Investor’s Lens

Investments are more than just financial transactions; they’re the culmination of unique perspectives, objectives, and strategies. Every investor, regardless of their background or affiliation, comes with their distinct set of priorities, risk tolerances, and expectations. Recognizing these varying lenses is crucial to structuring a mutually beneficial investment deal.

Angel Investor

The personal touch of an angel investor is a significant departure from more institutional forms of investments. Angel investors, often seasoned entrepreneurs or professionals, are driven by a genuine desire to mentor and support nascent businesses. For startups, this means not only acquiring funds but also benefiting from invaluable advice and connections. An example that springs to mind is Chris Sacca, who, apart from providing capital, offered strategic guidance to early-stage companies like Twitter and Instagram. When dealing with an angel investor, startups should focus on building a trust-centric relationship, emphasizing mentorship and shared visions.

Institutional VC

Institutional venture capitalists operate with a laser-focused objective: substantial returns on their investments. These entities are driven by rigor, research, and a keen sense of market dynamics. The story of Sequoia Capital’s investment in WhatsApp is a case in point. The massive $19 billion acquisition by Facebook led to returns that far exceeded the firm’s initial stake. When courting institutional VCs, companies should be prepared for meticulous due diligence, clearly defined exit strategies, and hard negotiations on terms.

Corporate Venture

Corporate venture capital is a strategic game. Here, large corporations aren’t just looking for financial returns but also synergies, innovations, and competitive advantages. When Google Ventures invested in Uber, it wasn’t just about the potential profitability of the ride-sharing market. The alignment with Google’s broader interests in transportation, mapping, and technology was evident. Companies seeking corporate venture funds should highlight potential integrations, joint ventures, or synergies that might be of interest to the parent corporation.

Investor Spotlight: Average Fund Amounts

Angel Investors:

Typical Range: $25,000 to $500,000

Venture Capital (Early-stage):

Typical Range: $500,000 to $5 million

Venture Capital (Later-stage):

Typical Range: $5 million to $50+ million

Corporate Venture:

Typical Range: $1 million to $100 million+

Crowdfunding

Treading the waters of crowdfunding brings a company face-to-face with a diverse array of minor stakeholders. Unlike traditional investments, the control exerted by these stakeholders is often limited, making it a relatively more democratic form of raising funds. Pebble, the smartwatch brand, is an illustrious example. By raising over $20 million on Kickstarter, Pebble not only secured funds but also validated its market demand. When opting for crowdfunding, it’s essential to craft a compelling narrative, provide transparent updates, and manage the expectations of a vast investor base.

Family and Friends

Perhaps the most delicate of all investment avenues is sourcing funds from family and friends. These transactions are intertwined with emotional ties and past relationships. The early days of Amazon come to mind, where Jeff Bezos sourced funds from close family, providing them with substantial returns when the company soared. While the potential for high rewards exists, so does the risk of strained relationships. Companies should ensure clear communication, legally binding agreements, and, most importantly, uphold the trust placed in them by their closest circle.

Understanding the perspective of investors isn’t just about recognizing their financial goals; it’s about appreciating their motivations, expectations, and the value they bring beyond capital. By tailoring investment structures to align with these unique lenses, companies can forge partnerships that stand the test of time and market volatility.

The Recipient’s Reality

Diving into the flip side of the investment equation, we come face-to-face with those on the receiving end – the companies. Each company, at its unique stage and within its distinct industry, faces varying challenges, growth trajectories, and objectives. It’s essential to recognize that while investors come with their own sets of goals, the recipient’s reality often defines the boundaries and sets the tone for how any investment is structured.

Early-stage startups

The bustling world of startups is often characterized by agility, ambition, and a pressing need for capital. At this nascent stage, flexibility can be as crucial as the cash injection itself. However, it’s a delicate balance. For instance, consider the tale of Oculus VR. Before it was a household name, Oculus required capital to bring its vision to life. When they chose to crowdfund, they not only acquired necessary funds but also retained significant control and flexibility, allowing them to eventually catch the eye of Facebook, which acquired them for $2 billion. The lesson? Early-stage startups must judiciously weigh immediate capital needs against long-term growth aspirations.

Growth-stage businesses

For businesses that have established a firm footing and are looking to expand, the investment landscape alters considerably. Here, the tug-of-war is between securing substantial capital to propel forward and retaining enough control to manage that growth effectively. A classic case is that of Airbnb. In its growth phase, the company cleverly structured its investments, enabling it to raise substantial sums while still navigating its growth trajectory with a clear vision. It’s pivotal for growth-stage businesses to draft investment structures that serve their expansion blueprint without stifling their operational essence.

Large corporations

Unlike their younger counterparts, large corporations often aren’t driven primarily by the allure of capital. Instead, they seek strategic alignments, partnerships, and synergies. Think of Disney’s acquisition of Pixar. While a significant financial transaction, at its core, it was a strategic move aimed at rejuvenating Disney’s animation division. Large corporations need to carefully align investment opportunities with their broader corporate strategies, ensuring that every deal brings more to the table than just capital.

Distressed companies

Treading on shaky grounds, distressed companies present a unique set of challenges and opportunities. Desperate times often call for urgent funding, potentially tipping the scales in favor of the investor. Kodak, once a giant in the photography world, faced rapid decline with the advent of digital photography. In its struggle, it sought multiple investments and partnerships, many of which came with stringent terms, reflecting the company’s precarious position. For distressed companies, it’s imperative to secure lifelines that offer a genuine chance at rejuvenation, even if it means ceding more control than desired.

Mature, steady businesses

Mature companies, having weathered many a storm, often seek funds for specific projects, innovations, or to maintain market leadership. Their investment narratives are less about survival and more about strategic growth or diversification. IBM’s pivot into cloud computing is a testament to this. Instead of resting on its laurels, IBM saw the shift in the tech landscape and invested heavily in this new direction. Mature businesses need to structure their investments to bolster existing strengths or pioneer into promising new territories, all while safeguarding their legacy and core competencies. In summary, the recipient’s lens is as multifaceted as the investment landscape itself. Recognizing the specific challenges and aspirations of the recipient company can go a long way in crafting investment structures that are not just beneficial but truly transformative.

![Law in the Digital Age: Exploring the Legal Intricacies of Artificial Intelligence [e323]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/WhatsApp-Image-2023-11-21-at-13.24.49_4a326c9e-300x212.jpg)

![Unraveling the Workforce: Navigating the Aftermath of Mass Layoffs [e322]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Untitled-design-23-300x212.png)

![Return to the Office vs. Remote: What Can Employers Legally Enforce? [e321]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Pasha_LSSB_321_banner-300x212.jpg)

![Explaining the Hans Niemann Chess Lawsuit v. Magnus Carlsen [e320]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/LAWYER-EXPLAINS-7-300x169.png)

![California v. Texas: Which is Better for Business? [313]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Pasha_LSSB_CaliforniaVSTexas-300x212.jpg)

![Buyers vs. Sellers: Negotiating Mergers & Acquisitions [e319]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Pasha_LSSB_BuyersVsSellers_banner-300x212.jpg)

![Employers vs. Employees: When Are Employment Restrictions Fair? [e318]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Pasha_LSSB_EmployeesVsEmployers_banner-1-300x212.jpg)

![Vaccine Mandates Supreme Court Rulings [E317]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/WhatsApp-Image-2022-02-11-at-4.10.32-PM-300x212.jpeg)

![Business of Healthcare [e316]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Pasha_LSSB_BusinessofHealthcare_banner-300x212.jpg)

![Social Media and the Law [e315]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/WhatsApp-Image-2021-10-06-at-1.43.08-PM-300x212.jpeg)

![Defining NDA Boundaries: When does it go too far? [e314]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Pasha_LSSB_NDA_WordPress-2-300x212.jpg)

![More Than a Mistake: Business Blunders to Avoid [312] Top Five Business Blunders](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Pasha_LSSB_Blunders_WP-1-300x212.jpg)

![Is There a Right Way to Fire an Employee? We Ask the Experts [311]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Pasha_LSSB_FireAnEmployee_Website-300x200.jpg)

![The New Frontier: Navigating Business Law During a Pandemic [310]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Pasha_LSSB_Epidsode308_Covid_Web-1-300x200.jpg)

![Wrap Up | Behind the Buy [8/8] [309]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Pasha_BehindTheBuy_Episode8-300x200.jpg)

![Is it all over? | Behind the Buy [7/8] [308]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/iStock-1153248856-overlay-scaled-300x200.jpg)

![Fight for Your [Trademark] Rights | Behind the Buy [6/8] [307]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Fight-for-your-trademark-right-300x200.jpg)

![They Let It Slip | Behind the Buy [5/8] [306]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Behind-the-buy-they-let-it-slip-300x200.jpg)

![Mo’ Investigation Mo’ Problems | Behind the Buy [4/8] [305]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/interrobang-1-scaled-300x200.jpg)

![Broker or Joker | Behind the Buy [3/8] [304] Behind the buy - Broker or Joker](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Joker-or-Broker-1-300x185.jpg)

![Intentions Are Nothing Without a Signature | Behind the Buy [2/8] [303]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/intentions-are-nothing-without-a-signature-300x185.jpg)

![From First Steps to Final Signatures | Behind the Buy [1/8] [302]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/first-steps-to-final-signatures-300x185.jpg)

![The Dark-side of GrubHub’s (and others’) Relationship with Restaurants [e301]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/When-Competition-Goes-Too-Far-Ice-Cream-Truck-Edition-300x201.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown of Internet Law & the Subscription Business Model [e300]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Ultimate-Legal-Breakdown-of-Internet-Law-the-Subscription-Business-Model-300x196.jpg)

![Why the Business Buying Process is Like a Wedding?: A Legal Guide [e299]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/futura-300x169.jpg)

![Will Crowdfunding and General Solicitation Change How Companies Raise Capital? [e298]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Will-Crowdfunding-and-General-Solicitation-Change-How-Companies-Raise-Capital-300x159.jpg)

![Pirates, Pilots, and Passwords: Flight Sim Labs Navigates Legal Issues (w/ Marc Hoag as Guest) [e297]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/flight-sim-labs-300x159.jpg)

![Facebook, Zuckerberg, and the Data Privacy Dilemma [e296] User data, data breach photo by Pete Souza)](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/data-300x159.jpg)

![What To Do When Your Business Is Raided By ICE [e295] I.C.E Raids business](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ice-cover-300x159.jpg)

![General Contractors & Subcontractors in California – What you need to know [e294]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/iStock-666960952-300x200.jpg)

![Mattress Giants v. Sleepoplis: The War On Getting You To Bed [e293]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/sleepopolis-300x159.jpg)

![The Harassment Watershed [e292]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/me-2-300x219.jpg)

![Investing and Immigrating to the United States: The EB-5 Green Card [e291]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/eb-5-investment-visa-program-300x159.jpg)

![Responding to a Government Requests (Inquiries, Warrants, etc.) [e290] How to respond to government requests, inquiries, warrants and investigation](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/iStock_57303576_LARGE-300x200.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Employee Dress Codes [e289]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Ultimate-Legal-Breakdown-Template-1-300x159.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Negative Online Reviews [e288]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Ultimate-Legal-Breakdown-Online-Reviews-1-300x159.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Social Media Marketing [e287]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ultimate-legal-breakdown-social-media-marketing-blur-300x159.jpg)

![Ultimate Legal Breakdown: Subscription Box Businesses [e286]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/ultimate-legal-breakdown-subscription-box-services-pasha-law-2-300x159.jpg)

![Can Companies Protect Against Foreseeable Misuse of Apps [e285]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/iStock-505291242-300x176.jpg)

![When Using Celebrity Deaths for Brand Promotion Crosses the Line [e284]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/celbrity-300x159.png)

![Are Employers Liable When Employees Are Accused of Racism? [e283] Racist Employee](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Are-employers-liable-when-an-employees-are-accused-of-racism-300x159.jpg)

![How Businesses Should Handle Unpaid Bills from Clients [e282] What to do when a client won't pay.](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/How-Businesses-Should-Handle-Unpaid-Bills-to-Clients-300x159.png)

![Can Employers Implement English Only Policies Without Discriminating? [e281]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Can-Employers-Impliment-English-Only-Policies-Without-Discriminating-300x159.jpg)

![Why You May No Longer See Actors’ Ages on Their IMDB Page [e280]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/IMDB-AGE2-300x159.jpg)

![Airbnb’s Discrimination Problem and How Businesses Can Relate [e279]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/airbnb-300x159.jpg)

![What To Do When Your Amazon Account Gets Suspended [e278]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/What-To-Do-When-Your-Amazon-Account-Gets-Suspended-1-300x200.jpg)

![How Independent Artists Reacted to Fashion Mogul Zara’s Alleged Infringement [e277]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/How-Independent-Artists-Reacted-to-Fashion-Mogul-Zaras-Alleged-Infringement--300x159.jpg)

![Can Brave’s Ad Replacing Software Defeat Newspapers and Copyright Law? [e276]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Can-Braves-Ad-Replacing-Software-Defeat-Newspapers-and-Copyright-Law-300x159.jpg)

![Why The Roger Ailes Sexual Harassment Lawsuit Is Far From Normal [e275]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/WHY-THE-ROGER-AILES-SEXUAL-HARASSMENT-LAWSUIT-IS-FAR-FROM-NORMAL-300x159.jpeg)

![How Starbucks Turned Coveted Employer to Employee Complaints [e274]](https://www.pashalaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/iStock_54169990_LARGE-300x210.jpg)