Get to know us

We represent businesses. That’s all we do.

oh, and we love it!

We love what we do.

Whether we’re reviewing a lease for your next space or stepping in to

save a deal that’s about to fall apart, we’re in it because we care

about helping your business grow and succeed. There’s nothing better

than helping build something solid—something that draws in the right

talent, brings in capital, and protects what you’re working so hard to

build.

We get close to our clients. We’re not just your lawyers; we’re your

partners. The kind who know your business, anticipate what’s coming,

and give real, strategic advice that matches where you're headed.

And we don’t charge by the hour. You pay for the outcome and the

value, not every time you send an email or jump on a call.

Our team is made up of people who live this mindset, and we’re proud

to work with clients who do too.

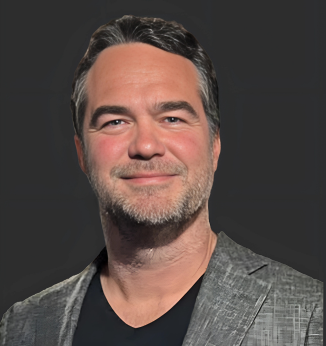

Pasha Law started in 2008 in San Diego because Nasir Pasha wanted a

different kind of law firm. One built around trust, relationships, and

meaningful outcomes. While others were counting hours, he was more

interested in making legal support truly valuable to businesses. So,

he started a firm that did exactly that.

Since then, we’ve grown, not just in size, but in the way we show up

for our clients and each other. That growth brought us to Houston in

2013, and we’ve kept moving forward from there. Through it all, we’ve

stayed focused on building a team and culture that puts people first

and believes in doing things the right way.